Ms. Gritskova, Ms Prinz, Sergey Prokofiev is one of the most famous Russian composers of the 20th century. But he is hardly known as a composer of songs, at least not in Central Europe. Is there a neglect of Prokofiev’s songs in Russia as well, or is this primarily a non-Russian phenomenon and then perhaps mainly due to the language barrier?

The Lied does not play a central role in Prokofiev’s oeuvre, although there are some fantastic jewels among his songs, and, by working on this genre, he was able to refine the lyrical qualities of his musical language. Even in Russia, the songs are not performed as often as Prokofiev’s piano or orchestral works or songs by classical Russian composers, like Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov. Outside Russia, these songs are almost unknown, certainly also because of the language barrier. But the music reflects the meaning of the poetry so precisely, both emotionally and in terms of content, that one can feel and understand very well what it is all about, when listening with open heart. It helps of course that Naxos kindly provides the lyrics in English and German translation in the booklet and online.

Ms Gritskova, you are also active as an opera singer. Did you immediately recognize ‘your’ Prokofiev, whom you knew from his operas, also in his songs or did you have to get used to it?

Prokofiev’s musical language is unmistakable and immediately recognizable in all of his works, but in the songs his brush paints even more finely and precisely, and as an interpreter you have to take care for the nuances and colours of every phrase, no matter how short it is.

Prokofiev’s musical language is unmistakable and immediately recognizable in all of his works, but in the songs his brush paints even more finely and precisely, and as an interpreter you have to take care for the nuances and colours of every phrase, no matter how short it is.

How did it come to the idea to record these rather rarely recorded Lieder for Naxos?

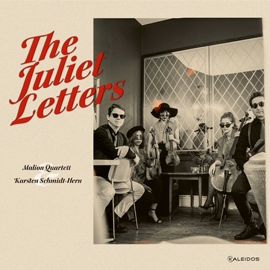

The idea to work together with Naxos came from pianist Maria Prinz, who had already recorded for them with flautist Patrick Gallois and the wonderful singer Krassimira Stoyanova and was enthralled by the work with this label. Our first production started with more traditional repertoire – Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Rachmaninov (Russian Songs, Naxos 8.573908). We are very grateful to the label for giving us the chance to record rarely played repertoire, namely Prokofiev and, next coming up, Shostakovich (release planned for October 2020). This repertoire is particularly close to our hearts and opens up even more possibilities for us to find our own interpretation style.

Ms Prinz, it is noticeable that Prokofiev composed many of the songs on the album after he had completed large, opulent opera projects. In this context, at least I was amazed by the apparently reduced piano accompaniment of the selected songs to the most essential, but which, precisely because of this, have a very haunting effect. What challenges does this pose for you as a pianist?

Although the piano accompaniment is in many cases laconic, it is very complicated in terms of harmony and, as is generally the case with Prokofiev’s piano writing, it is technically anything but comfortable to play. The composer himself was a fantastic pianist with large hands.

Piano accompaniment is essential for creating the atmosphere and commenting on the unspoken in the text. As always when making music with singers, I get inspired by the timbre of the voice and then try to find my own colours and accents, to continue telling the story by rounding it off, commenting on it, or even questioning it. Speaking fluently Russian enables me to really understand the text in all its nuances in the original language.

Especially the early Prokofiev is known to the general public as a very brilliant, virtuoso piano composer, especially through his first three piano concertos. Now one gets to know him from a completely different side in these songs. Is this lyrical point of view representative for the Lied composer Prokofiev or is there also in the Lied genre that brilliant, virtuoso Prokofiev, whom we just don’t get to hear on this album because of the chosen repertoire?

As Ms Gritskova already mentioned, and as Wilhelm Sinkovicz emphasizes in his contribution to the booklet, through the songs one gets to know Prokofiev as a melodist. This is certainly characteristic for most of his songs. Whereby very virtuoso passages (as for example in ‘Ugly Duckling’ or in ‘Hello’, the fourth of the five songs on poems by Akhmatova op. 27, ‘The Little Grey Dress’ op. 23 or ‘Remember Me!’ op. 36 No.4) occur again and again and remind us of the brilliance and elementary power of his piano works.

While I listened to the album, I had the impression that Prokofiev pursued an individual song style very early on, which is hardly based on the very influential German Lied tradition. But one might think that one can already hear some echoes of the French tradition – does this already represent a mental approach of the composer in regard to his exile in Paris, which began just a little later?

A French influence can very well be detected, e.g. in the impressionistic-sounding ‘Trust me’ op. 23 No. 3, in some of the songs based on texts by Akhmatova or in ‘Remember Me!’. This may not only be due to the fact that he was drawn to Paris, but perhaps also to the composer’s character, to whom elegance, lightness and a certain detachment were always important.

The late Prokofiev can be heard on the album with children’s songs, arrangements of folk songs and Duo versions of oratorial arias. This seems at times a bit well-behaved compared to the emotionally charged early songs. Did the song genre with its direct combination of text and music made it increasingly difficult for the composer in a time when Stalin’s ‘cultural politics’ had an idealistic equalisation in mind?

Exactly! As we know, Prokofiev returned voluntarily and probably somewhat starry-eyed to the Soviet Union in 1936 and died on 5 March 1953, the same day as Stalin. The resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party from February 10. 1948, represents a turning point in the relationship between political power and the compositional creativity not only for Prokofiev, but also for Shostakovich. This was a campaign against « bourgeois decadence and modernism », which was preceded by years of attacks against formalists, reactionaries (including Anna Akhmatova), and which branded everything that was not popular, simply knitted and ideologically conformist and declared composers to be « enemies of the people ». It is therefore not surprising that Prokofiev, who by the way never distinguished himself by exposing himself as an adversary of power, probably bowed to this trend – at least in a genre that is not among the most representative of his oeuvre.

Nevertheless, the content of some songs, is to be understood in a sharply ironic way, as for example in « Anjutka ». The lyrics say that if every cleaning woman only educates herself and reads enough books, she could also rule the country. This irony also finds its expression in the music of this song.

Your next project will be a Shostakovich Lieder album. If you compare the compositions by Prokofiev and Shostakovich in this genre: Where do you see similarities, where differences?

As we know, Shostakovich and Prokofiev were contemporaries, even though Shostakovich survived Prokofiev by more than 20 years and thus faced a completely different reality in his last creative period. Nevertheless, the two could not be more different in their nature, in their attitude to life and art. Shostakovich was, without a doubt, the more « Russian », the more introverted, the more vulnerable of the two. And this also manifested itself in his song writing. As in all matters, Shostakovich dealt also with the Lied genre, with a missionary seriousness and dedication, seeking inspiration by different cultural traditions. His cycles Greek songs, Spanish songs and Jewish songs bear witness to this. The style of both composers is unmistakably individual, original and contemporary in different ways. Both are united by the selection of valuable avant-garde poetry (in Prokofiev’s case, for example, by Anna Achmatova, in Shostakovich’s by Marina Tsvetaeva) and also a certain affinity for irony and satire is common for both of them.

Finally, a word on the current state of the cultural sector: a few weeks ago, you, Ms. Gritskova, took part in the opera gala of the German AIDS Foundation, which was transformed into a digital event due to corona restrictions, and to which the participating artists made contributions with small home concerts from the living room at home, so to speak. How did you experience this unusual situation?

It is of course as difficult and sad for me, as it is for all my colleagues. The lockdown came shortly before the resumption of Tri sestri by Peter Eötvös at the Vienna State Opera, which I had been so much looking forward to. The gala concert of the young ensemble of the Vienna State Opera to mark the end of Dominique Meyer’s era and also my role debut as Preziosilla in La forza del destino at the Klosterneuburg Opera Festival fell victim to Corona. Now all hopes are focused on the autumn and on how opera theatres and concert organisers will be using creative solutions to make an almost normal operation possible. We need the stage, we need our audience, and we can’t wait to get back to our profession and live out our vocation in the service of art!