Bartok empfand seine atonal geschriebenen Violinsonaten trotzdem als tonartgebunden, was beim Hören nicht jeder sofort nachvollziehen mag. Und sie haben auch etwas Siamesisches, so hat es der Musikwissenschaftler Pierre Citron einmal gedeutet. Denn beim thematischen Material gehen beide Instrumente völlig getrennte Wege und treffen sich nur an wenigen markanten Punkten. So sind sie bildlich am Rücken verbunden, können sich aber nie sehen.

In dieses Umfeld der Entwicklungen der musikalischen Moderne ab 1900 passt auch das dritte Stück, die Mythen von Szymanowski. Sie entstammen der Phase, in der er seine musikalische Sprache entwickelte, bei der er Klangfarben priorisierte.

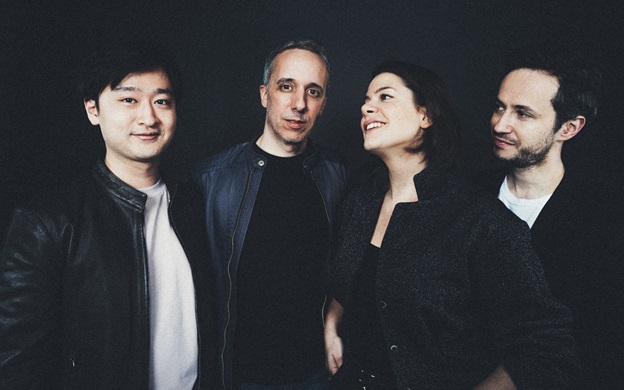

Seit zwei Jahren spielen Zimmermann und Choni nun zusammen. Der arrivierte Geiger und der junge Pianist gestalten die Musik mit packender Energie und mit ausgeprägt gestaltendem Ansatz, so dass sie alle drei Werke zu Kunstwerken der Kammermusik formen. Dank dieses Zusammenwirkens prägen sie den gemeinsamen Weg, so dass man die siamesische Situation bei Bartok gar nicht wahrnimmt. Sie lassen mit dieser Intensität nicht nur die bei der Entstehung moderne Musiksprache hören, sondern entlocken den Werken Farbgebungen, die expressionische Züge heraufbeschwören. Und Zimmermann nimmt mit edel ausgeprägtem Ton der Musik die Schärfe, die die Stücke unangenehm klingen lassen würde.

Choni, von sich aus schon technisch brillant und mit Tiefsinn interpretierend, zeigt sich hier auch als feinfühliger und mit dem Partner aufs Engste in der Sicht auf die Interpretationen fühlender und ausführender Pianist.

Auch wenn die Aufnahme teilweise bereits nach nur einem Jahr des gemeinsamen Weges eingefangen wurde, haben sich hier zwei Musiker gefunden, die in der Beherrschung ihres Instrumentes und in der Interpretation der Musik einander bestens verstehen.

Bartok considered his atonal violin sonatas nevertheless to be key-based, which may not be immediately apparent to everyone when listening to them. They also have something Siamese about them, as musicologist Pierre Citron once said. This is because the thematic material of the two instruments follows completely separate paths, meeting only at a few distinctive points. They are thus figuratively connected at the back, but can never see each other.

The third piece, Szymanowski’s Myths, also fits into this context of developments in musical modernism from 1900 onwards. They originate from the phase in which he developed his musical language, prioritizing timbres.

Zimmermann and Choni have been playing together for two years now. The established violinist and the young pianist perform the music with gripping energy and a distinctive interpretative approach, transforming all three works into masterpieces of chamber music. Thanks to this interaction, they shape their joint path in such a way that Bartok’s Siamese situation is not even noticeable. With this intensity, they not only allow the modern musical language of the time to be heard, but also elicit colors from the works that evoke expressionistic traits. And Zimmermann, with his nobly distinctive tone, takes away the sharpness that would make the pieces sound unpleasant.

Choni, who is technically brilliant in his own right and performs with profound thoughts, also shows himself here to be a sensitive pianist who feels and performs in close harmony with his partner in his view of the interpretations.

Even though the recording was made after only one year of working together, these two musicians have found each other and understand each other perfectly in their mastery of their instruments and their interpretation of music.