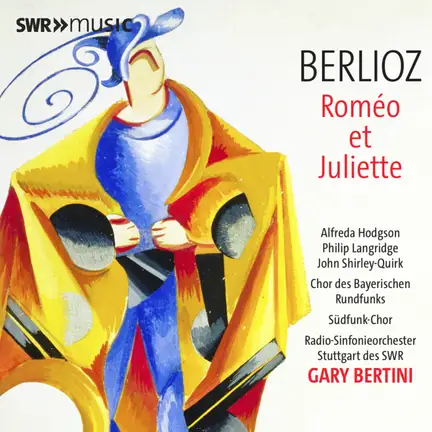

Berlioz hat Shakespeare bewundert. In seinen Schriften schwärmt er von ihm als dem König aller Poeten. In seiner Vokalsymphonie Roméo et Juliette, die keine einzige Shakespeare-Zeile enthält, verneigt er sich wörtlich und musikalisch ebenfalls vor dem Dichter.

Soviel Schwärmerei und Huldigung versagt sich Gary Bertini in seiner Berlioz-Lektüre. Den Orchesterklang gestaltet er nie zu üppig, hält ihn eher schlank, setzt auf eine feine Nuancierung mit warmen, leuchtenden Farben. Insgesamt verleiht er dem tödlichen Liebesdrama um Romeo und Julia einen eher lyrischen, sinnlichen Charakter – womit er vielmehr an Shakespeare anknüpft. Selbstverständlich geht es in dieser Veroneser Familienfehde nicht ohne Drama und Leidenschaft. Sie setzt das Orchester energisch, engagiert um.

Nicht unterschlagen werden sollen allerdings die Schwächen dieser Aufnahme. Mögen die Solisten auch stimmlich gut sein, so tut ihr englischer Akzent der Rhetorik nicht immer gut. Die exzellenten Chöre ihrerseits wirken oft distant, was zum Teil wohl dem Alter der Aufnahme geschuldet ist, der es an Frische mangelt. Dennoch bleibt es unter dem Strich eine gute, stimmige Interpretation dieses selten gespielten Berlioz-Werkes.

Berlioz admired Shakespeare. In his writings, he raves about him, calling him the king of all poets. In his vocal symphony Roméo et Juliette, which contains no lines from Shakespeare, Berlioz pays homage to the poet verbally and musically.

However, Gary Bertini refrains from such enthusiasm and homage in his interpretation of Berlioz. He never allows the orchestral sound to become overly lush, preferring to keep it lean while focusing on subtle nuances and warm, luminous colors. Overall, he gives the tragic love story of Romeo and Juliet a lyrical and sensual character, thus drawing more on Shakespeare. Of course, the Veronese family feud is not without drama and passion. Bertini interprets it energetically and with commitment.

However, the weaknesses of this recording should not be overlooked. While the soloists are vocally good, their English accents do not always do the rhetoric justice. The excellent choirs often seem distant, probably due to the age of the recording, which lacks freshness. Nevertheless, this is a good, coherent interpretation of this rarely performed work by Berlioz.

In an interview, Edgaras Montvidas said that Luciano Pavarotti is his role model. This may be true for opera, but when it comes to song, the Lithuanian tenor does not need a role model. He is a creative individual who can stand on his own two feet with his own ideas and creativity. His new album, featuring works by Chausson, Britten, and Saint-Saëns that French poets set to music, is the best example of this. Of particular note is Britten’s Illuminations, based on texts by Arthur Rimbaud.

Montvidas’s interpretation of these texts is a feat of rhetorical artistry. The tenor delves deep into the words and music, allowing the moods to guide him as he shapes a wide variety of timbres. He makes this piece, as well as the other two, his own by singing with a finely nuanced timbre free of any mannerisms. In this way, the Lithuanian tenor illuminates a wide range of emotions, from deepest vulnerability and unspeakable despair to Arthur Rimbaud’s surrealism, poetic visions, and sensual eroticism.

However, all of Montvidas’s efforts would be in vain if he did not have musical partners who speak the same musical language, bring the same intensity, and offer atmospheric and gripping interpretations of this repertoire in unison. These partners are Modestas Pitrėnas, the Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra, and the Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra.