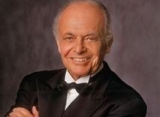

Der Dirigent Lorin Maazel stellt auf seiner Facebook-Seite Überlegungen zu Operninszenierungen an. Wie nicht anders zu erwarten, ist sein Aufsatz ein Frontalangriff auf das Regietheater, das Opern oft bis zur Unkenntlichkeit entstellt. Maazel sagt, die Rolle des Regisseurs wie auch des Dirigenten sei es, darüber zu wachen, die Vorgaben von Komponisten und Librettisten in bestmöglicher Form umzusetzen und ihre Absicht so klar wie möglich zu machen, in ständigem Respekt vor der Arbeit der Komponisten und Librettisten. Alles andere sei pervers, sagt Maazel. Hier ist sein Text im englischen Original:

Opera Staging Madness

by Lorin Maazel

PART ONE

A great number of opera lovers are becoming increasingly alienated from an art form that has nourished the spirits and minds generations of people… opera: the ultimate fusion of song and sound, of word and fancy, a visceral corporal soul language second to none in breadth and depth of thought and emotion.

At the risk of stating the obvious, of postulating the pedestrian, may I approach the subject of the staging and musical interpretation of an opera applying logic and common sense?

An opera is a Gesamtkunstwerk, i.e. a ” total art work; an artistic creation, that synthesizes the elements of music, drama, spectacle, dance, language, social mores, dress, body language ” and all other aspects at any given moment of the recounted story as it is set to music.

The librettist tells the story, sets it in a time period, in a cultural and social context. The composer finds the appropriate sounds, turn of phrase, thematic material to project his/her interpretation of the emotions engendered by the story. The stage director’s task to flesh out in a convincing manner the essential thrust of the story

as interpreted by the composer. The conductor’s task is to bring to life the implications of the music in a meaningful and vibrant way.

The roles of both stage director and conductor are essentially custodial, bringing into play only those actions which heighten and make clearer the intentions of librettist and composer, actions which at every turn must respect and honor the librettist and the composer. To do otherwise is to pervert and despoil the work of masters. The egos of stage director and conductor (and his/her psychological problems) are never ever to come into play.

An opera stage is not a psychiatrist’s couch.

PART TWO

In Part One of my comment regarding the Philistinism of some present day opera staging concepts,

I wrote: ‘The roles of both stage director and conductor are essentially custodial.’ ‘Custodial’ challenges, does not restrict, the fantasy of Stage and Music Director.

Two examples: the first, Giorgio Strehler’s 1980 production at La Scala of Verdi’s Falstaff…end of Scene Four when a gigantic laundry basket, presumably containing Falstaff hiding and suffocating inside, is dumped over a restraining barrier into the river Thames.

In a whimsical stroke of staging genius, Giorgio had a huge wave wash over the stage three seconds after the laundry basket “hit” the river! (Never mind that at least one performance, the water flowed over the raked stage into the orchestra pit!). Sheer staging heaven, this! No need to turn Shakespear’s jocund reveler Falstaff into a retired sumo wrestler at a Caracas brothel.

The second example: Keita Asari’s now legendary staging in 1986 at La Scala of Madame Butterfly. About an hour before the opera began, a Japanese country-style house could be seen being ‘constructed” authentically block by block, rock garden and all. At precisely 7pm, the lights dimmed, the conductor (me at the time) walked out, bowed and gave the down beat.

The audience has been imperceptibly drawn into the timelessness of an ancient culture. Cio-Cio San’s suicide was staged with a delicacy that brought tears to my eyes at every performance: no disembowelment, simply a gentle poke of her fan, which seemed to release a vermilion carpet that slowly unravelled over twenty feet of stage….her life’s blood.

Now THAT’S staging genius.

No need to desecrate the refinement of a tender soul in a fragile ancient culture and given soul-life by Puccini by casting Butterfly as a hash-slinger in a San Diego diner.

PART THREE

What can be done to safeguard an endangered art form?

If it is believed that an opera audience can be cowed into tolerating any abuse of text and music for fear of seeming to be old-fashioned, conservative, recidivist (who wants to be thought of as not with it, not up to speed, uncool), the manipulators, axe-grinders and mafiosi, given a free hand, cheerfully assault the art form.

One of the challenges for an opera house General Manager is to sell out the house. The ultimate say-so rests with the audience. If their beloved world of opera is being degraded and ridiculed (not too long ago. a stage director who publicly derided the art form of opera, staged one, with the cast dressed as monkeys), what to do? Boo? Certainly not.

The singers and musicians do their best under trying circumstances and their work should be respected.

What then?

Follow the example of a gentleman who, after the First act of a Shakespeare play presented at an international festival and directed by someone who proudly said he had never read one and engaged non-professionals to “act”, stood up and said in a ringing voce “George, let’s go”. All but thirty people left the theater.

You won’t get your money back but if the General Manger reads on Facebook often enough that the Opera House he/she is managing is losing its audience, he/she will soon change course.

Another suggested action is pre-emptive in nature: if you read that a new production at your favorite opera house will be given of La Boheme set in a Nepalese fish market with the Sex Pistols in the orchestra pit conducted by Sarah Palin, don’t go.

Lorin Maazel