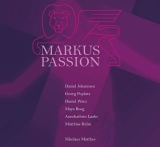

Am 23. März 1731 findet in Leipzig die Erstaufführung von J.S. Bachs Markuspassion auf ein Libretto von Picander statt. Seit der Aufführung einer von Bach angefertigten Neufassung ist die Partitur verschwunden. Überliefert ist lediglich der Text von Picander, den Nikolaus Matthes mit einer neuen Musik ausgestattet hat.

Im Begleitbuch legt der Komponist gleich die Karten auf den Tisch. Seine Komposition atmet Bachs Geist, ist jedoch kein Imitat. Sie hat mit manch zeitgenössischen harmonischen Wendungen auch eine ganz persönliche Note. Matthes setzt allerdings sehr bewusst auf eine barocke Klangsprache, ansonsten Text und Musik zu sehr auseinanderdriften würden. Wissend, dass Bach und Picander eng zusammengearbeitet haben, sollte die Musik auf der gleichen rhetorischen Tonleiter spielen.

Das Resultat ist eine dramaturgisch stimmige Komposition, die uns in die Leidensgeschichte Jesu eintauchen lässt. Als Zuhörer ist man nicht stiller Betrachter, sondern wird quasi Teil des Geschehens, das ständig zwischen innerem Aufruhr, schmerzhaftem Leiden, Hoffnung, Zuversicht und Angst hin und her wankt.

So setzt Matthes etwa im ersten Teil mit der Arie ‘Mein Heiland’ einen ersten Ruhepunkt, nach dem er die Handlung bis dahin zügig vorangetrieben hat. Diesen innigen, betrachtenden Augenblick kleidet er in eine zarte Arie, ein intimer Dialog zwischen Tenor und Traverso. Vor dem Schlussteil – die Grablegung – hören wir eine feinsinnige Sinfonia.

Die teilweise packende Dramatik (z.B. die Aufforderung des Volkes ‘Kreuzige ihn…’) sowie die starke Emotionalität halten die Spannung über die gesamte Spieldauer hoch.

Dass dem so ist, dazu trägt das leidenschaftlich spielende Ensemble bei, das alle Saiten des barocken Musizierens kennt. Musikalische Rhetorik und Textdeklamation gehen Hand in Hand, die Musik ist stets mit Leben gefüllt, hat ihre stürmischen Momente, ist aber ebenso berührend und bewegend. Sänger und Instrumentalisten spielen nicht bloß die Noten, sie reflektieren, kommentieren, formen Text und Musik, geben dem Erzählten Struktur, befeuern Arien, Dialoge und Chorsätze mit suggestiver Kraft.

The first performance of J.S. Bach’s St. Mark’s Passion to a libretto by Picander took place in Leipzig on March 23, 1731. Since the performance of a new version prepared by Bach, the score has disappeared. All that remains is Picander’s text, to which Nikolaus Matthes added new music.

In the accompanying book, the composer lays his cards on the table. His composition breathes the spirit of Bach, but is not an imitation. It also has a very personal touch with some contemporary harmonic twists. However, Matthes deliberately opts for a baroque musical language, otherwise the text and the music would drift too far apart. Knowing that Bach and Picander worked closely together, the music should be on the same rhetorical scale.

The result is a dramaturgically coherent composition that immerses us in the story of Jesus’ passion. As a listener, you are not a silent observer, but rather a part of the action, which constantly oscillates between inner turmoil, painful suffering, hope, confidence and fear.

In the first part, for example, Matthes sets an initial point of calm with the aria ‘Mein Heiland’, after having driven the action forward rapidly up to that point. He dresses this intimate, contemplative moment in a tender aria, an intimate dialogue between tenor and traverso. Before the final section – the Entombment – we hear a subtle Sinfonia.

The sometimes gripping drama (e.g. the crowd’s demand ‘Crucify him…’) and the strong emotionality keep the tension high throughout the work.

The passionate ensemble, which knows all the strings of baroque music-making, contributes to this. Musical rhetoric and text declamation go hand in hand, the music is always full of life, has its stormy moments, but is also touching and moving. Singers and instrumentalists don’t just play notes, they reflect, comment, shape text and music, give structure to the narrative, fuel arias, dialogues and choral movements with suggestive power.