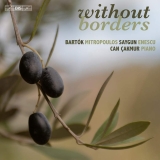

Über Bela Bartoks Sonate hat man gelesen, sie sei barbarisch. Und es gibt Interpreten, die dies mit Kraftmeierei zu unterstreichen versucht haben. Der junge türkische Pianist Can Cakmur geht einen anderen Weg. In einem gewissen Sinne glättet er die Musik, ohne ihr ihre rhythmische Eigenart zu nehmen. Er spielt ohne die Schwere und die Kraft von Argerich und selbst Kocsis, gleichzeitig klarer, tänzerischer, flüssiger und, wie ich finde, spannender. Der zweite Satz wird nicht ganz so mysteriös wie bei Argerich, aber insgesamt stimmungsvoller und ist dem traditionellen Ursprung der Musik näher. Der 3. Satz, der bei Argerich viel Unruhe zeigt, wird von Cakmur mit viel Leichtigkeit gespielt und erinnert an einen Drachen, der sich im wechselnden Wind in anmutigen Kapriolen über den Himmel bewegt.

Passacaglia, Intermezzo e Fuga von Dimitri Mitropoulos entstand 1924 in Sykia (Korinth). Das 15 Minuten dauernde Werk besteht aus einer Passacaglia von ca. 10 Minuten, gefolgt von einem kurzen Intermezzo und einer etwa drei Minuten langen Fuge. Es sei ein Versuch – so steht es auf der Mitropoulos-Webseite -, die strenge barocke Form mit atonalen, expressionistischen Mitteln zu renovieren, und zwar « unter dem direkten Einfluss der antiromantischen Prinzipien der jungen Klassizität von Ferruccio Busoni ». Dies setzt Can Cakmur in einer spannenden Interpretation brillant um.

Der türkische Komponist Ahmed Adnan Saygun (1907-1991) konnte ab

1928 mit einem Stipendium der türkischen Regierung in Paris bei Vincent d’Indy studieren, hat in den Dreißigerjahren Jahren aber auch als Assistent von Bela Bartok Anatolien bereist und dort wie auch später in anderen Teilen der Türkei Volksmusik erforscht. Sowohl sein Studium bei d’Indy wie auch der besondere Klang der türkischen Volksmusik bestimmen seine Tonsprache. Seine Klaviersonate entstand als letztes Werk kurz vor seinem Tod. Sie wurde bisher nur einmal in der Türkei aufgenommen und war international nicht auf Tonträgern zu erhalten. Can Cakmur gelingt eine sehr spannende Auseinandersetzung mit dem etwas sperrigen, insgesamt eher Hoffnungslosigkeit vermittelnden Werk, dem der Pianist aber im langsamen Satz schöne Stimmungen abgewinnen kann. Dieses Lento führt zu einem wie desorientiert, vorübergehend sogar heiteren, im Grunde aber auch abgeklärten Finalsatz.

Die fantasievolle Dritte Sonate von George Enescu beendet das Programm. Sie entstand in einer Zeit persönlicher Probleme, nachdem seine Lebensgefährtin Maruca einen Nervenzusammenbruch erlitten hatte, « der sie für den Rest ihres Lebens an den Rand des Wahnsinns brachte ». Enescu schrieb in einem Brief an Edmond Fleg, den Librettisten von Oedipe: « Ich tröste mich, indem ich mich in die Komposition flüchte. Das Ergebnis ist eine neue Klaviersonate, frisch nach Oedipe entstanden. Sie ist voller Heiterkeit, ganz im Gegensatz zu der Atmosphäre, die sie umgibt ».

Can Cakmur spielt den ersten Satz mit federleichtem Klang. Den Mittelsatz, Andantino cantabile, färbt er nur ganz leicht melancholisch und, seinen Wurzeln in der rumänischen Volksmusik gemäß, sehr kantabel, atmosphärisch und voller zartem Charme. Den letzten Satz, Allegro con spirito, hat man einfach beschwingt und fröhlich gehört. Bei Cakmur wird er mysteriös und ist geprägt von einer leichten Unruhe, als habe der Pianist tiefer in die Seele des Komponisten geschaut als dieser das selber getan hatte, und so kann er dessen ‘Flucht’ auch als Flucht darstellen.

Und so haben wir es erneut mit einer Schallplatte zu tun, die den jungen türkischen Pianisten Can Cakmur als einen ungemein intelligenten und persönlichen, die Materie tief ergründenden Interpreten zeigt, bei dem es nicht Beiläufiges und nichts Leichtfertiges gibt, sondern alles seine Raison d’être hat. Das reicht von eigenen Booklettexten bis eben zu diesen Interpretationen, die mit all ihrer Logik imponieren und trotz vorausgegangener harter Arbeit, Erarbeitung eigentlich, ungemein frisch und spontan wirken.

Und sollte mir jemand erwidern, Cakmur sei als mehrfacher ICMA-Preisträgern bei Pizzicato halt immer auf der Gewinnnerseite, so frage ich jeden, der sowas sagt, er solle mir einen Grund nennen, weshalb ich diese herausragende Platte nicht mit einem Supersonic auszeichnen sollte.

One has read about Bela Bartok’s sonata that it is barbaric. And there are interpreters who have tried to underline this with a lot of force. The young Turkish pianist Can Cakmur takes a different approach. In a certain sense he smoothes the music without taking away its rhythmic peculiarity. He plays without the heaviness and power of Argerich and even Kocsis, at the same time clearer, more dance-like, more fluid and, I think, more exciting. The second movement doesn’t get quite as mysterious as Argerich’s, but is altogether more atmospheric and closer to the music’s traditional origins. The 3rd movement, which shows much restlessness in the Argerich recording, is played with much ease by Cakmur and is reminiscent of a kite moving in graceful capers across the sky in the changing wind.

Passacaglia, Intermezzo e Fuga by Dimitri Mitropoulos was written in 1924 in Sykia (Corinth). The 15-minute work consists of a passacaglia of about 10 minutes, followed by a short intermezzo and a fugue of about three minutes. It is an attempt – according to Mitropoulos’ website – to renovate the strict Baroque form with atonal, expressionistic means, « under the direct influence of the anti-romantic principles of Ferruccio Busoni’s young classicism. » This is brilliantly realized by Can Cakmur in an exciting interpretation.

In 1928, the Turkish composer Ahmed Adnan Saygun (1907-1991) got a scholarship from the Turkish government to study with Vincent d’Indy in Paris. In the 1930s, he also traveled to Anatolia as an assistant to Bela Bartok and researched folk music there as well as later in other parts of Turkey. Both his studies with d’Indy and the special sound of Turkish folk music determine his musical language. His piano sonata was written as his last work shortly before his death. It has been recorded only once in Turkey and has not been available internationally. Can Cakmur succeeds in a very exciting performance of the somewhat unwieldy work, which on the whole conveys rather hopelessness, but from which the pianist is able to extract beautiful moods in the slow movement. This Lento leads to a final movement that seems disoriented, temporarily even serene, but also basically detached.

The imaginative Third Sonata by George Enescu closes the program. It was written at a time of personal problems, after his partner Maruca suffered a nervous breakdown « that brought her to the brink of madness for the rest of her life. » Enescu wrote in a letter to Edmond Fleg, the librettist of Oedipe, « I console myself by taking refuge in composition. The result is a new piano sonata, freshly written right after Oedipe. It is full of cheerfulness, quite contrary to the atmosphere that surrounds it. »

Can Cakmur plays the first movement with feathery playfulness. He colors the middle movement, Andantino cantabile, only very slightly melancholy and in keeping with its roots in Romanian folk music, very cantabile, atmospheric and full of delicate charm. The last movement, Allegro con spirito, has been heard simply buoyant and joyful. With Cakmur it becomes mysterious and is marked by a slight restlessness, as if the pianist had looked deeper into the composer’s soul than the composer himself had done, and so he is able to portray Enescu’s ‘escape’ really as such.

And so we are once again dealing with a recording that shows the young Turkish pianist Can Cakmur as an immensely intelligent and personal interpreter who deeply understands the material, for whom there is nothing casual and nothing light-footed, but everything has its raison d’être. This ranges from his own booklet texts to these very interpretations, which impress with all their logic and, despite previous hard work, are incredibly fresh and spontaneous.

And should anyone say that Cakmur, as a multiple ICMA award winner, is always on the winning side at Pizzicato, I ask anyone who says that to give me a reason why I should not award this outstanding record with a Supersonic.