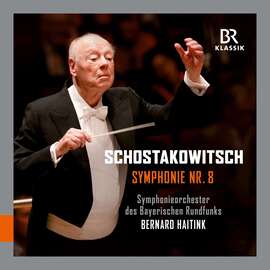

Maestro Haitink had an exceptionally broad repertoire. But Bruckner and Mahler had a very special positon within this repertoire. And so did Shostakovich. Do you know where this attraction to Shostakovich’s music came from?

In the 1970s it was still quite unusual for “Western” conductors to conduct Shostakovich, and he was not familiar with all of the symphonies, although he already knew the 8th and some others. But he began a cycle with the London Philharmonic, and gradually recorded all of them for Decca, with both the LPO and the Concertgebouw Orchestra. I think he was fascinated by the mixture of darkness and sometimes quasi-military “triumphalism”, a lot of which was ironic, of course.

Mrs. Haitink, I know some conductors wives, and very often they are in a privileged situation of being asked by her husbands to comment on rehearsals or performances. Was that the case with Maestro Haitink?

Mrs. Haitink, I know some conductors wives, and very often they are in a privileged situation of being asked by her husbands to comment on rehearsals or performances. Was that the case with Maestro Haitink?

This is dangerous….but yes! He didn’t always like to hear my comments if they were critical, but he said that he always took them on board. That doesn’t mean he changed anything, only that he listened!

Would he also consult you about proposals from orchestras or from recording companies?

We would discuss practical issues – how do we get from X to Y, is there enough space in the schedule? – but not really repertoire. He was often asked by orchestras to do the repertoire which was most associated with him, because that’s what people wanted to hear from him, rather than something he necessarily wanted to do himself. But of course, very often, these wishes coincided.

How was your husband at home? Could he be stressed by deadlines, maybe in the fear of not being ready for some work? And if so, what would you do?

The favourite part of his work, which he loved the most, was sitting in his study, with a score in front of him. That was the thing he feared missing the most when he was about to retire – although in fact, he didn’t stop doing that, he just studied different things, like string quartets. He was rarely stressed by deadlines, because he never left things until the last minute. I don’t think I ever saw him less than well-prepared; he would have thought that unforgiveable. Leaving home for a work period was another thing – he was stressed by the thought of travel, especially long distances. And even after 60 years of conducting, he was still nervous before every performance, to whatever degree.

Did he conduct differently in the recording studio than in the concert hall?

It’s difficult for me to say, because in his last 30 years of conducting virtually all recordings were “live”, taken from concerts. But he told me that he liked that much better than studio recording, which was all he did in his early days; he found it less “artificial”. I’m sure he tried to get the feeling of a performance in the studio, but it’s not always easy.

Can you please tell us something about the relation Maestro Haitink had with the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks.

Oh, he loved them! This is no flattery, but they were one of his absolute favourite orchestras to work with. They have a great virtuosity, a wonderful sound and also great musical flexibility. He would say, “You can ask anything of them, and they will do it,” and always with a positive attitude. He had a long history with them, doing major recording projects such as The Ring and other operas for EMI, and performed regularly with them over many decades. And in recent years many of those performances were recorded, with their excellent sound engineers and producers, with whom he also had a very good relationship.

Do you have any memories of the concerts with Shostakovich’s Eight in 2006 in Munich?

Do you have any memories of the concerts with Shostakovich’s Eight in 2006 in Munich?

I wish I could say that I do, but…..

It’s well known that your husband liked to buy new scores and to start from a clean print. Why would he do that?

He liked to be confronted with a “clean sheet”, to see the composer’s directions without any pre-conceptions, even his own, and look again as though with a fresh pair of eyes. And marking up the scores again was a good way of refreshing his knowledge of a work which might have been very familiar to him, sometimes seeing things which perhaps he hadn’t noticed before. But when it came to the rehearsals and performances, he would use the scores he had used before, because he had them specially enlarged so that he could read them easily.

What did upset your husband most?

Well obviously, telephones. And gratuitous coughing – we all know some people cannot help it, but there are some who can, but nonetheless seem to enjoy clearing their throats; although Bernard would also say that sometimes when people were coughing, it was his fault, because it meant he hadn’t created the right climate of concentration which keeps everybody really focused. When that happens, it’s extraordinary how nobody seems to feel the need to cough.

And what gave him the greatest pleasure?

Of course, he was immensely privileged to have the opportunity to conduct great masterworks with some of the most wonderful orchestras in the world, and incredible soloists. And he was aware of that, and humbled by it. But I don’t think a day went by that he didn’t also listen to chamber music, or piano music, whether Schubert sonatas or Lieder, Bach, the quartets of Beethoven (or indeed Shostakovich, he thought them amongst the best of his works) or something like the Debussy Preludes – French music was a great passion of his. He was also a great reader – everything from Homer to Goethe to Montaigne to contemporary American and British writers. So he was never bored!