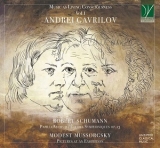

Es war lange ruhig um den 1955 geborenen russischen Pianisten Andrei Gavrilov. Er, dessen Karriere nach dem Gewinn des Tchaikovsky-Wettbewerbs im Jahre 1974 zweimal abrupt unterbrochen wurde – 1979-1984 wurde er vom Sowjet-Regime in die Isolation gezwungen, 1993-2001 zog er sich wegen einer Lebenskrise zurück – hatte vor 1993 für EMI und Deutsche Grammophon aufgenommen. Jetzt startet der mittlerweile in der Schweiz lebende Künstler eine neue Serie von Aufnahmen für das Label Da Vinci Classics. Sie soll wohl eine Art endgültige Sicht auf Werke werden, die der Pianist früher schon für andere Labels aufgenommen hat.

In Schumanns Papillons gibt es sehr nachdenkliche Passagen, aber auch solche, wo die Musik schwerelos abhebt und leicht dahinschwebt, wie eben ein Schmetterling. Doch es geht ja in diesem Stück nicht um Schmetterlinge, sondern um das Romanfragment Flegeljahre von Jean Paul. Die beiden Hauptfiguren des Romans sind Walt Harnisch (eine eher ruhige Dichter-Natur) und sein Bruder Vult (ein draufgängerischer Flötenvirtuose und brillanter Tänzer). Beide lieben dieselbe Frau, deren Wahl zwischen Vult und Walt auf einem Maskenball entschieden wird. Der Titel Papillons bezieht sich – wie Schumann erläutert haben soll – auf das bunte « Durcheinanderflattern auf einem Faschingsball“.

Walt und Vult waren auch die Vorbilder für Schumanns gespaltenes Alter Ego (Florestan und Eusebius). Also sind schwebende Passagen zwangsläufig mit kräftiger und aufgewühlter Musik zu kontrastieren. Das macht Andrei Gavrilov sehr deutlich und mit größter Klarheit. Das mag auf Kosten der Kohärenz gehen, aber das ist gerade bei Schumann kein Kriterium, weil es Gavrilov darum geht, mit eher vertrackter Poesie und viel Hintergründigkeit Schumanns Außer-sich-Sein durchschimmern zu lassen.

Die Etudes Symphoniques differenziert Gavrilov sehr, und so kommt auch in dieser Komposition, nicht zuletzt durch höchst ungewöhnliche Phrasierungen und Akkordauffächerungen, viel Zerrissenheit zum Ausdruck. Gavrilov nutzt etwa das Allegro Marcato der 4. Etüde, um dieses Stück ausdrucksvoll trotzig werden zu lassen. Der Kontrast zum nachfolgenden quirligen und wie beschwipst torkelnden Scherzando wird so umso grösser. Es mündet in ein Agitato, das wirklich erregt ist und zu einem wie gejagt wirkenden Allegro molto führt. Florestan und Eusebius sind hier in voller Aktion, auch im Finale, bei Florestans Kampf gegen die engstirnigen, spießbürgerlichen Philister, das entsprechend zornig vorgetragen wird.

Kein Zweifel, Gavrilov legt mehr Inhalt, mehr Ausdruck in die Etudes Symphoniques als die meisten anderen Pianisten.

Seine Kunst der Färbung, seine Beherrschung dynamischer Werte und der Rhythmik bringt auch in Mussorgskys Bildern einer Ausstellung sehr viel Action und ganz besonders ausgeprägte Stimmungen. Und in dem Ganzen fasziniert das stupend klare und durchhörbare Spiel des Pianisten, der diese CD mit ‘Music as Living Consciousness’ bezeichnet, mit dem Zusatz Vol. 1. Hoffentlich wird sein Projekt noch etliche weitere so hervorragende Programme bringen.